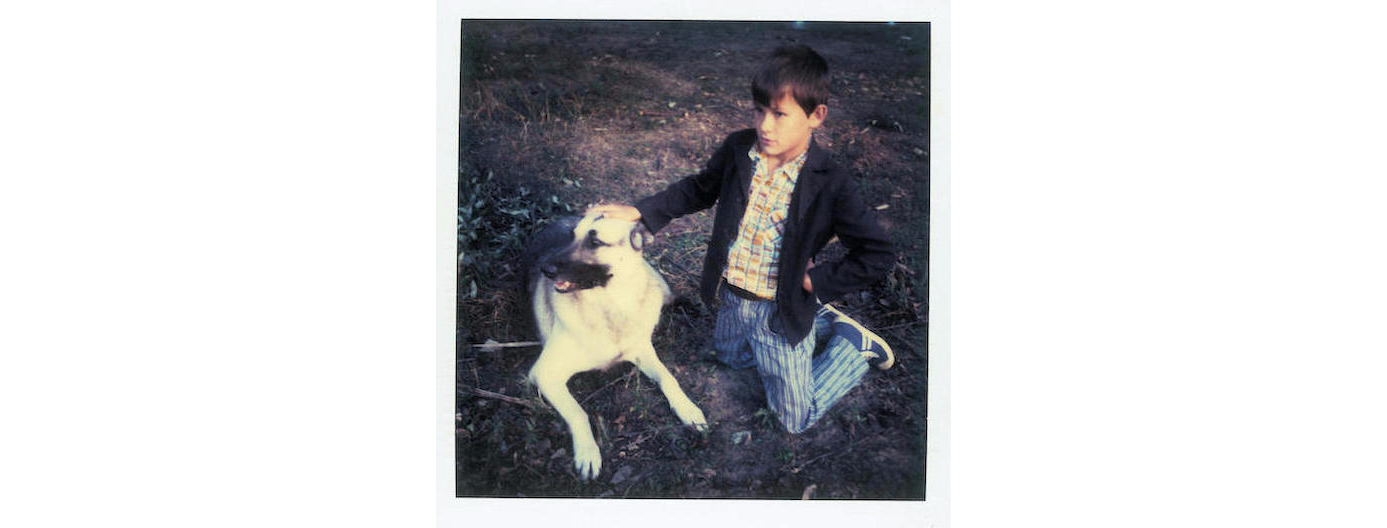

Diane Arbus: In the Beginning, exhibits 100 images made from 1956 - 1962, is full of poor compositions, confusing pictures, and near-miss pictures, which we know because we have already seen the great ones that came later. This show should be reassuring to all beginners, when they see that even Diane Arbus made bad photographs.

Though the show nearly doubles the number of Arbus images in print, it makes me wonder whether we have really been missing an important view of this extraordinary artist, not available until now. These are, after all, photographs she never intended anyone to see. They were the early ones, the rejects. And though her standards were extraordinarily high, and someone else might have agreed to show some of them, the fact remains that she did not.

Even after two biographies, we know relatively about Diane Arbus, and have seen very little of her work. Arbus, an artist highly regarded by her peers, but not familiar outside New York art and publishing circles, died a suicide in 1971, age 48. In 1972 (or immediately, in museum time) the Museum of Modern Art held a one woman show, using images that Arbus had selected and approved for exhibit during her lifetime. Everyone considered these images mature works of a genius at the height of her powers. The unofficial catalogue, Diane Arbus, with “Identical Twins, Roselle New Jersey, 1967” on the cover, has never been out of print (and according to Arthur Lubow, her highly regarded biographer, it has sold half a million copies, making it one of the best-selling art books of all time). Until recently the 80 images from that book were all we saw; Diane Arbus: Magazine Work, (published in Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar and New York magazine, among others) and Untitled (images made in 1969 and 1970 at a home for retarded women, chosen for publication by her daughter, Doon) added roughly 100 more pictures to the group. That’s all we saw for over 30 years. Her haunting story, and her scarce and matchless pictures, made Arbus an icon for artists, feminists, and outsiders, and a very high earning figure in the art market.

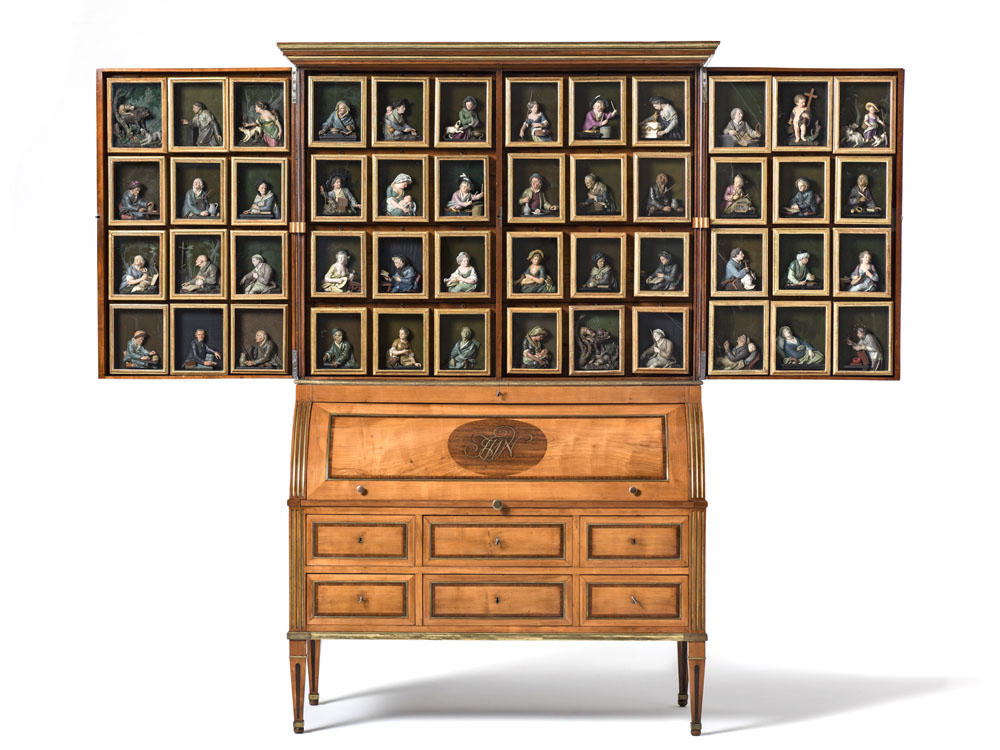

In 2003, Revelations, an enormous exhibition and accompanying publication by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, opened Arbus’s life to public view, including a reproduction of her darkroom, and a wall of her books with an installation that felt like a shrine. The book itself is a kind diary/scrapbook, printing letters, diaries, and many pictures we had never seen, most in small sizes, like historical snapshots. The best part was getting to see the images never seen before, made throughout her career. We saw images made as early as 1956, when she began in earnest to make art photographs, using a 35mm camera. We saw her earliest efforts with the square format 2-1/4 camera, which she started to use in 1962, and used till the end of her life. There were many more “ordinary” people in those pictures — New York ladies out shopping, couples and families sitting together, young women at home. In this context, all images betrayed the Arbus signature style. Most were prints that already existed in the archive. In a very few cases, the estate decided to make new prints, essentially adding to the canon of existing images. (This very rare practice has also been done with work from the estate of Garry Winogrand.) It struck me then that the Arbus estate was essentially printing money, for once on the market, these new prints would immediately become as rare and valuable as the work we already knew.

In 2007, the Arbus Estate selected the Met to be the permanent repository of the Diane Arbus Archive, a voluminous collection, including negatives, prints, papers, correspondence, and library.

Now the Met returns to this early work for an exhibition, all made before 1964, and almost all the images made with a 35mm camera. We see familiar subjects — freaks, transvestites, girls dressed nearly alike, eccentrics of all kinds — and the ordinary people, somehow revealed to have more significance than we could ever imagine. In the few instances when the show includes a square format print — as with Child with a Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962 — you want to cheer. It’s a breakthrough! You have found your way!

Around the time Arbus made this picture, she applied for a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, and emphasized the documentary, historical nature of her work.