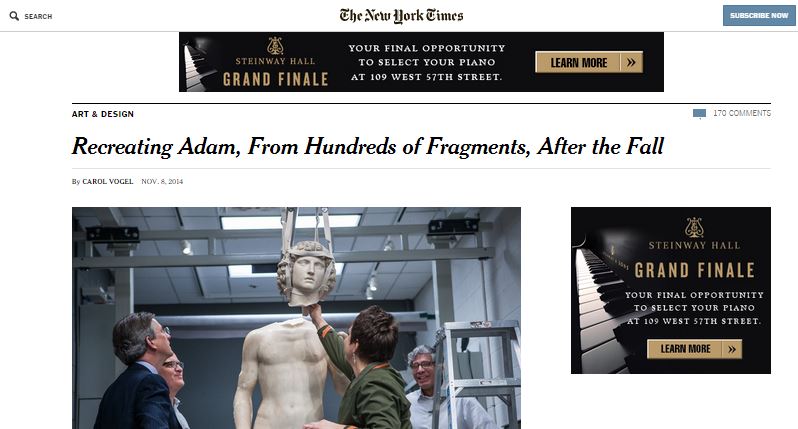

The separated head and torso looked disconcertingly familiar to me when they appeared in a photo on the front page of The New York Times on Sunday, November 9th. “Recreating Adam, From Hundreds of Fragments, After the Fall.”

The history of how it happened, the secrecy that ensued, the resurrection, and finally, revelation is the plot of this terrifying tale of Tullio Lombardo’s great Renaissance marble masterpiece. I hadn’t felt able to speak about it in detail for 12 years. A promise is a promise.

After the fall, when the initial horror of the museum staff had worn off, but only slightly, a few of us, engineers , technicians and art specialists, were called upon to render professional opinions about what had gone wrong and what was going to be done about it. I and a colleague from this firm were led, as if to a chamber of horrors, into the conservation laboratory where the sculpture lay, shattered yet still magnificent .

The papers write of it as if it had been scattered in a thousand fragments across the marble floor of the Velez Blanco Patio at the Met, but I remember it as retaining recognition as a very late 15th century Lombardo, head and much of the torso and one leg intact. I can’t recall exactly because I had to turn over all my photographs immediately after our report was rendered. Those were the days before digital where nothing dies. I guess those were the “28 recognizable pieces” that Met conservator Jack Soultanian mentioned in the newspaper article. The rubble had been bagged and identified.

From time to time, from hushed voices, we learned a little about what was going on in the lab, but very little. Massive amount of research were undertaken by this firm and we traced the sculpture back to its original site. The Renaissance scholar on staff, Leatrice Mendelsohn, was amazing in her pursuit of all the critical information required to help me arrive at a value of the sculpture before the fall and how much the piece had lost in value because of the damage.

A few months later I sat at an endlessly long wood table in a secluded section of the Met of which I had not been previously aware, facing what seemed to be an endlessly long line of dark suited attorneys representing the multiple organizations and firms involved in the disaster. Oddly enough, I don’t remember being scared because I was so overwhelmed by the grandeur of the setting, with light streaming down behind the group of what appeared to be judge types sitting to my left. I felt like it was an old Warner Brothers film about the trial of Charles the First.

Okay, not to prolong this because, after all, I survived and am writing this blog now. I mean, I wasn’t the one at fault anyway. I didn’t push Adam off his pedestal. The fact that its six foot three, one thousand pound marble body had been standing for so many years on a modest wooden pedestal might have had something to do with the disaster.

So it was with relief that I found that the Met has decided to open the floodgates of information, always a wise course to take, and one that suddenly seems in favor at major museums nationally. So much better than having misinformation leaking out in bits and pieces and that can prove far more detrimental than a simple admission and explanation.

I wonder if reality shows have been influencing all of us.

Written by Elin Lake-Ewald