Dr. Elin Lake-Ewald

Ph.D., ASA, FRICS

One of the fascinating aspects of being a professional in the Art World is that you get invited to a lot of events at organizations you have never heard of before but which often have considerable followings. And then you feel “out of it” because you’ve never heard of them before, but also “in” because now you have.

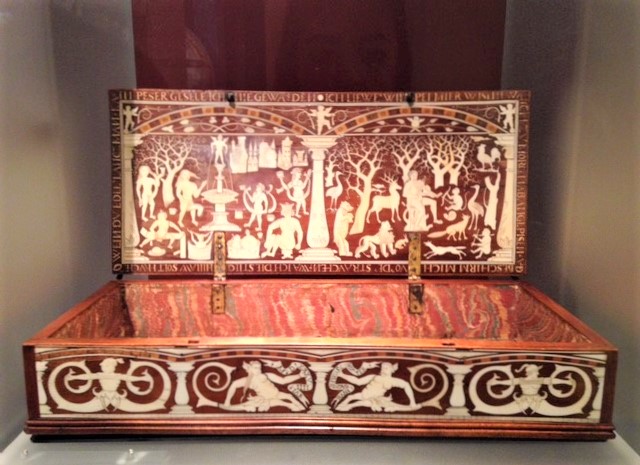

Last Friday I attend the National Symposium of Collectors For Connoisseurship, held at the Sacerdote Auditorium of the Uris Center at the Metropolitan Museum. Titled Patronage and Collecting: Then & Now, I was addressed by curators at the MET, the Frick and the Morgan Library, followed by a panel of speakers representing different aspects of the market. Perhaps in an audience of diverse backgrounds different people took away different messages, but the main one seemed to me was that collectors in the past were often deeply involved in the intellectual and aesthetic aspects of their collections, while today’s collector may be seduced by branding and name recognition.

Will brick & mortar galleries continue as they have or will art fairs and online sales take over? We were all interested in that question which, of course, cannot be resolved in one symposium or even in 50, which I am certain will probably occur in the next year. What makes it so necessary for people to keep chewing over the same question so often without reaching for a resolution? Sort of like the talk talk talk re the current plethora of stories about abuse of women in business. A thousand stories so far, but haven’t heard one suggestion about a real solution.