Relative Value: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance

On view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

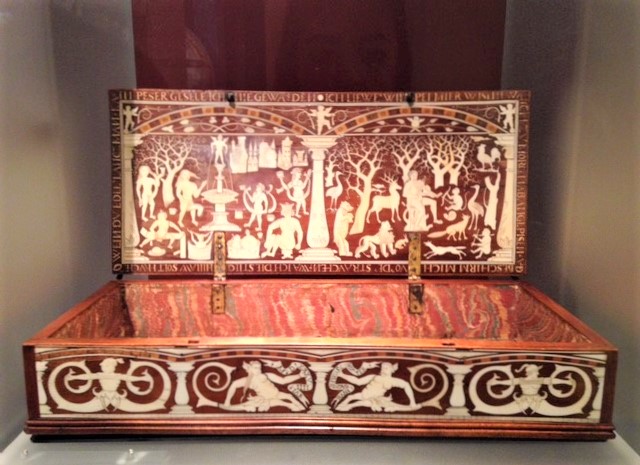

62 masterpieces of varying media and function that invite the examination of historical worth and relative value systems of the era

The Rest on the Flight into Egypt

Follower of Quentin Metsys (Netherlandish, mid-16th century) and Master of the Liège Disciples at Emmaus (Netherlandish, active mid-16th century), ca. 1540

The most original show at the MET these days is on the first floor – back of the building.

Maybe the curators have tired of listening to museum-goers speculate out loud how much a particular painting or ivory object is worth.

Okay, if that’s what they’re interested it let’s give it to them, but let’s not make it too easy or too obvious. We will inform them as to what a particular artwork is worth in the equivalent of a coin of the realm in the 16th-17th centuries. Mostly in cow power.

The need to equate art with money – or what the Northern Renaissance collectors would pay for a precious item in terms of what was of approximately the same value in more mundane objects – that’s the crux of the show and more than well worth the visit.

How much is that gorgeous goblet worth, that gold chalice with intricately sculpted and inch high jeweled and elaborately costumed figures so meticulously carved that each finger is individually rendered? I’d say 255 cows. And that crystal bird from Nuremberg with ruby eyes? That’s 275 cows and worth every moo. Suppose a baron wanted a woodcut by Albrecht Dürer for his wall (although it was probably kept in an album in those days), he’d only have to come up with half a cow in payment. Not sure how that worked. Another object that’s not much more than a commoner’s earthenware vessel with a decorative lead glaze would have been an eighth of the value of a cow. Would that include prime ribs?

I like the idea of a new approach to arousing interest in the many gorgeous, but often overlooked objects in this treasure chest of a museum. The MET has created another way of showing us that there is so much of such interest within its metaphorical vaults that it isn’t absolutely necessary to bring in objects from elsewhere to excite the viewers. I would like to give my thanks to the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts and the curator(s) of the exhibition and the effort he/she made to think beyond the obvious and arouse new interest in old things that the Met owns. And, of course, for the audiences of 2017, it had to be about value – or do I mean price?